By William H. Freivogel

When Michael Brown crashed to the pavement on Aug. 9, he landed on ground that has a unique role in the nation’s centuries-long struggle over race, justice and law.

This is the land of Elijah Lovejoy, the Missouri Compromise, Dred Scott, the East St. Louis race riots and some of the nation’s most important legal fights over race. The landmark housing discrimination cases of Shelley v. Kraemer, Jones v. Mayer and Black Jack began here. And St. Louis had the nation’s biggest, most expensive school desegregation program.

So it is no surprise that this place is again a metaphor for the nation’s unfinished business involving race.

To understand this city’s importance in the national civil rights movement, one can look back 200 years to the Missouri Compromise, which tried to barter people’s freedom for peace in the union.

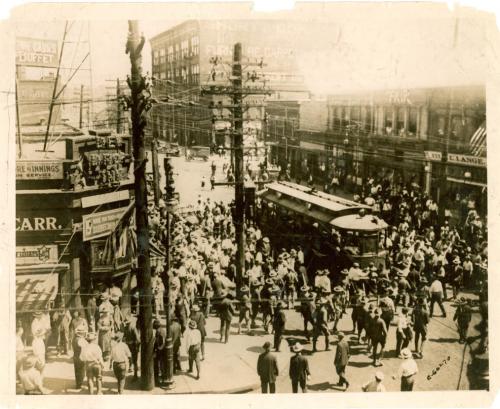

Or look back a century to the 1917 East St. Louis race riots when about 100 blacks were killed, some thrown from a bridge into the Mississippi River.

Or look back half a century to Percy Green’s protest climb up the Arch, unmasking of the Veiled Prophet and “stall-in” at McDonnell Douglas Corp., which led to an important legal battle over job discrimination.

Or 35 years to the creation of the nation’s largest, most costly and most successful inter-district school desegregation plan in which 13,000 students escaped one-race classrooms and showed higher graduation and college-going rates.

Or 20 years to the all-out legal crusade fought by then Attorney General Jay Nixon -- on the heels of an equally passionate crusade by his predecessor John Ashcroft -- to eliminate the St. Louis and Kansas City school desegregation plans. Nixon won a Supreme Court decision bringing down the curtain desegregation in Kansas City and elsewhere, but he failed to end St. Louis’ program.

Or 17 years to then Sen. John Ashcroft blocking African-American judge Ronnie White from the federal bench.

Or 750 days to Brown’s graduation from unaccredited Normandy High School where students faced educational chaos created by state officials.

Or 730 days ago to Brown dying on a street next to a mostly segregated housing Canfield Green complex, a few miles from the legal symbols of the nation’s fight for housing integration. A short distance away are Black Jack, the town created to keep out blacks, Paddock Woods, where Joseph Lee Jones wanted to buy a home and the house on Labadie that J.D. Shelley wanted to buy, but for a racial covenant barring sale to blacks.

The ghosts of these struggles – and many more – haunt this city as St. Louisans today turn to the problems left unsolved.

Yet St. Louis’ unique racial history is not entirely one of failure. Dred Scott won his case in the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis. Civil rights leaders won Shelley v. Kraemer and Jones v. Mayer, opening up housing to African-Americans. And the St. Louis-St. Louis County school desegregation program has given generations of white and black children a chance to meet in school.

Race, Justice and Law

Read the Constitution and there is a shock on the first page – the three-fifths compromise. Keep reading and you find protection for the slave trade and the fugitive slave provision.

Thirty years after the Constitution patched over slavery, the nation tried again with the Missouri Compromise. Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine as a free state. Congress banned slavery in the portion of the Louisiana Purchase above the southern border of Missouri.

St. Louis greeted passage, wrote historian Glover Moore, “with the ringing of bells, firing of canon” and a transparency showing “a Negro in high spirits, rejoicing that Congress had permitted slaves to be brought to so fine a land as Missouri.”

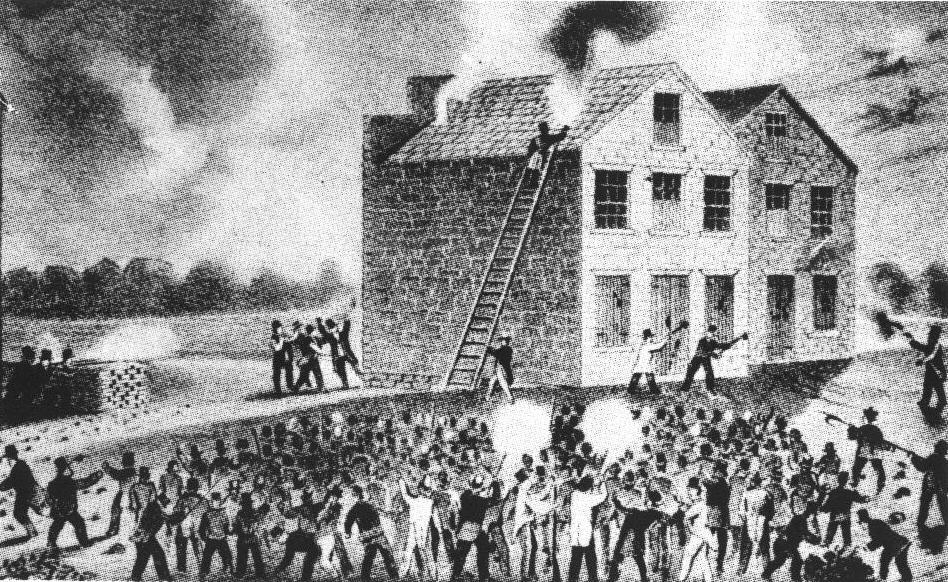

St. Louis was anti-slavery but people didn’t like abolitionists. Toughs from riverfront saloons chased Elijah P. Lovejoy out of St. Louis to free soil in Alton, Ill. There, in 1837, a mob killed him as he tried to protect his newspaper office. The mob threw the press into the Mississippi.

In 1847 Missouri passed a law making it illegal to teach blacks. “No persons shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of mulattos in reading or writing,” it read. A few brave teachers took skiffs into the Mississippi River to evade the law.

One of the slaves living in the St. Louis of that era was Dred Scott. In 1846 he and his wife Harriet, filed for their freedom arguing they had become free when a former owner took them to free soil.

In 1850 a Missouri judge ruled in Scott’s favor, but the Missouri Supreme Court ignored its precedents and kept Scott in slavery. It was worried about the growing power of abolitionists, remarking on the nation’s “dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery.”

In the most infamous decision in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roger Taney concluded in 1857 that blacks “are not included and were not intended to be included, under the word citizens in the Constitution.”

“We the people” did not include blacks who are so “inferior” that they had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because Congress had no power to ban slavery in the territories, the court ruled.

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas debated the Dred Scott decision. But it took the deaths of 620,000 Americans to settle the issue.

Settle the issue of slavery that is. Equality is taking longer.

Fighting for a place to live

In 1916 -- just before the deadly East St. Louis race riots -- St. Louisans voted by a 3-to-1 margin to pass a segregation ordinance prohibiting anyone from moving into a block where more than three-fourths of the residents were of another race.

Supporters said the law was needed"for preserving peace, preventing conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in the city of St. Louis.”

A leaflet with a photo of run-down homes said: “Look at These Homes Now. An entire block ruined by the Negro invasion….SAVE YOUR HOME! VOTE FOR SEGREGATION.”

St. Louisans also attached restrictive covenants to home deeds, preventing sale to blacks. Many trust indentures excluded “Malays” -- along with blacks and Jews -- because Malays were displayed in the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis.

By the end of World War II, blacks in St. Louis were mostly segregated within a 417-block area near Fairground Park, partly because of these restrictive covenants. About 117,000 people lived in an area where 43,000 had lived three decades earlier.

House on Labadie

J.D. Shelley challenged the covenants when he tried in 1945 to buy a house at 4600 Labadie that barred sale to "persons not of Caucasian race." Neighbors Louis and Ethel Kraemer, sought to enforce the covenant.

George L. Vaughn, a noted African-American lawyer, took Shelley's case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Vaughn said he wasn't seeking integration. "Negroes have no desire to live among the white people," he said. "But we were a people forced into a ghetto with a resultant artificial scarcity in housing."

In the 1948 decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, the United States Supreme Court outlawed judicial enforcement of racial covenants. The involvement of the state courts in enforcing the covenants made this a state action, not just private discrimination, the court said.

A year later, the city tried to integrate nearby Fairground swimming pool. Forty black children needed a police escort to leave the pool in what Life magazine called a “race riot.”

The Life story read, “In St. Louis, where the Dred Scott case was tried, the cause of racial tolerance seemed to be looking up last week. A negro police judge took office for the first time, and the Post-Dispatch hired its first Negro reporter. But when the city opened all of its swimming pools to Negroes on June 21…progress stopped….police had to escort 40 Negro swimmers through a wall of 200 sullen whites.”

The mayor immediately reimposed segregation at the pool. The city’s official report said it had been unfair to call the disruption a riot.

Discriminatory federal policies

Federal housing policies after World War II discriminated against blacks by subsidizing rapid expansion of all-white suburbs while building largely segregated public housing projects.

Carr Square was built for blacks and Clinton Peabody for whites. Pruitt-Igoe, built in the 1950s, was Pruitt for blacks and Igoe for whites. The project quickly became all black and symbolized the failure of public housing when it was blown up in the 1970s.

The words - “FHA financed” - in housing ads were code for blacks need not apply, writes Richard Rothstein in an Economic Policy Institute report on the root causes of Ferguson.

An FHA underwriting manual called for “protection against some adverse influences” adding “the more important among the adverse influential factors are the ingress of undesirable racial or nationality groups.”

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission, which came to St. Louis in 1970, concluded: “Federal programs of housing and urban development not only have failed to eliminate the dual housing market, but have had the effect of perpetuating and promoting it.”

Need for a playground

Suburban communities used exclusionary zoning to keep out black families. Howard Phillip Venable, a noted African-American eye doctor, was building a house in Creve Coeur in 1956 when the city refused to grant him a plumbing license.

Suddenly, the city discovered a need for a new park, and condemned the property for a playground. U.S. District Judge Roy Harper, notoriously opposed to civil rights, tossed out Venable's suit. The park stands today where the late doctor wanted to live.

A few years later, a black St. Louis bail bondsman had better success. In 1964, Joseph Lee Jones and his wife, Barbara, applied for a "Hyde-Park style" house in the Paddock Woods subdivision, five miles due north of the current Canfield Green apartments in Ferguson. Alfred H. Mayer Co. refused to sell the home.

Lawyer Sam Liberman took Jones’ case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Constitution protects "the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live," wrote the court, adding "when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it ... is a relic of slavery."

Shortly after Jones v. Mayer, the Inter Religious Center for Urban Affairs planned to build Park View Heights, integrated, subsidized townhouses in an unincorporated area of north St. Louis County near Paddock Woods. Local opposition developed in the area that was 99 percent white and residents incorporated as the city of Black Jack. The new town promptly passed a zoning ordinance that barred construction.

Harper threw out the challenge to this discriminatory zoning. A federal appeals court overturned the decision.

Judge Gerald Heaney, who was just as famous for his pro-civil rights decisions as Harper was notorious, wrote that when a law had a discriminatory effect, the burden is on the city to show it has a strong, non-discriminatory purpose. Black Jack hadn’t.

Although residential racial segregation has declined in St. Louis and most other cities, St. Louis is the seventh most racially segregated metropolitan area based on the 2010 census, ranking after other rust belt cities such as Milwaukee, New York/New Jersey, Chicago, Cleveland and Buffalo.

Leland Ware, a former St. Louisan and professor at the University of Delaware, says the 1968 Fair Housing law was largely a "toothless tiger" with weak enforcement. “Lingering vestiges of segregation remain in the nation’s housing markets that “perpetuate segregated neighborhoods.”

Not a story

In the early 1950s, a group of young civil rights activists – Irv and Maggie Dagen, Charles and Marion Oldham and Norman Seay – led a CORE sponsored sit-in of lunch counters in segregated downtown St. Louis.

Richard Dudman, a young reporter for the Post-Dispatch, ran across the protest and hurried back to the office with the big story.

The editors told the future Washington Bureau chief to forget it. They knew about the protests but weren’t writing about them because it might trigger violence. Avoiding a riot was a preoccupation at the paper where big glass windows near the presses were boarded up just in case.

There never was a riot, a fact often cited as a reason St. Louis never seriously grappled with race.

One reason there was no riot was the Jefferson Bank protests of 1963, the birthplace of that generation’s black leaders. William L. Clay, who went on to Congress, led the sit-in blocking the bank’s doors.

Clay showed that blacks got only a few hundred of the 23,000 downtown jobs at breweries, department stores, banks, insurance companies and newspapers.

Although Clay and other protesters were arrested, they won about 1,300 new downtown jobs.

Climbing the Arch

CORE’s tactics weren’t muscular enough for Percy Green, who started ACTION in 1964, calling for “direct action” to gain civil rights. He didn’t think the Jefferson Bank protesters had asked for enough jobs and he wanted to show that civil rights protesters would not be frightened off by the harsh court penalties on Jefferson Bank protesters.

Green attracted attention by climbing the partially built Gateway Arch, unmasking of the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan and filing a historic job discrimination case again McDonnell Douglas.

Green and a white friend climbed one leg of the Arch on July 14, 1964 to demand that 1,000 black workers be hired for the $1 million construction activity. There were no black workers on the Arch construction project. He followed up demanding 10 percent of the jobs at utility companies -- Southwestern Bell, Union Electric and Laclede Gas.

“Southwestern Bell had no telephone installers at the time,” he recalled in an interview. “Laclede Gas had no meter readers…..We managed to expose them to the extent that they had to start hiring blacks in those areas. I think the first black…telephone installer eventually retired as a top-notch official. At the time the excuse they gave for blacks not being telephone installers….was they felt that these black men would create problems by going into white homes. That’s what the president of the company said and a similar excuse was given me by the president of Laclede Gas.”

A month after Green’s protest at the Arch, McDonnell Douglas laid him off saying it was part of a workforce reduction. Green thought the company took the action for his climbing the Arch. ACTION held a stall-in near McDonnell Douglas to protest. Later, Green sued McDonnell. He lost, but the test laid out in the case made it easier for people to prove job discrimination.

In 1972, Green organized the unmasking of the Veiled Prophet. The Veiled Prophet ball was a relic of the Old South, with St. Louis’ richest leaders in business dressing up in robes that some people thought looked like Ku Klux Klan as debutantes paraded in evening gowns.

“We realized,” Green recalled, “that the chief executive officers who we had met with about these jobs also was a member of this organization and we put two and two together. No wonder these people don’t hire blacks because they are socially involved in these all-white organizations…. (And) they auctioned off their daughters…. The fact that I used that language was very disturbing to these people. Here these same chief executive officers, racist in terms of their employment, they also were sexist in not allowing their females to live their lives.”

In the late 60s, ACTION had its own black VP ball and the black VP and black queen would try to attend the ball. They would always be denied admission and arrested.

Then in 1972, a woman from ACTION, the late Gena Scott, lowered herself to the stage along a cable and umasked Monsanto’ executive vice president Thomas K. Smith. The city’s newspapers did not print Smith’s name. After that, the Veiled Prophet took steps to desegregate, but Green makes it clear that his group wasn’t seeking entry, but rather was trying to pressure top business leaders to provide more jobs for blacks.

Green was active in an effort to put video cameras in the hands of citizens a decade ago, thinking that was the only way to get a conviction of a police officer. When he heard about the death of Michael Brown, “deep down I felt this was another outright murder and is no different from what happened before. ….They (police) say they fear for their life, but at no time does a person fear for their life that they show any indication of taking cover….They say they fear for my life, boom, boom, boom.”

“None of this is new,” says Green. Law enforcement demonizing black men goes back to slavery, he said. The only way for law enforcement to gain the confidence of people“is for the Establishment to charge, convict and put in jail for long periods of time policemen who murder black folk, black males….Prosecuting attorneys should also be jailed for abuse of their authority (for) their conduct to allow for these policemen to get away with murder and then these judges who use their benches to justify policemen executing black males.”

Segregated schools

Missouri segregated its schools longer than most southern states. It wasn’t until 1976 that Missouri repealed its requirement of separate schools for “white and colored children.”

Segregation applied to the University of Missouri as well. In 1938 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Mizzou to admit Lloyd L. Gaines to its law school or to create separate one of equal quality. The state took the latter option, turning a cosmetology school at black Lincoln University into a law school. NAACP lawyers planned to challenge the separate school but Gaines disappeared without a trace on a visit to Chicago. It was an era when blacks were lynched at Columbia, Maryville and Sikeston.

Two of Missouri’s most prominent politicians over the past 30 years – Ashcroft and Nixon – crusaded as attorneys general against the big, ambitious school desegregation plans in St. Louis and Kansas City – the two most expensive in the country.

Minnie Liddell’s desire to have her son Craton attend the nice neighborhood school instead of being bused to a bad neighborhood led, ironically, to the nation’s biggest inter-district voluntary busing program sending about 14,000 black city students to mostly white suburban schools.

NAACP lawyer William L. Taylor had pulled together evidence of the complicity of suburban school districts in segregation. Many suburban districts had bussed their students to all-black St. Louis high schools. Kirkwood, for example, bussed its black students to Sumner.

In 1981, a canny judge and former congressman, William Hungate, put a gun to the head of the suburban districts. Either they would “voluntarily” agree to the inter-district transfer program or he would hear all of the evidence of inter-district discrimination and then order a single metropolitan school district.

That frightened suburban school districts and helped special master D. Bruce La Pierre, a Washington University law professor, persuade them to join the voluntary transfer program.

Ashcroft went to the Supreme Court trying to stop the plan, saying there was nothing voluntary about the court’s requirement that the state pick up the tab – which came to $1.7 billion over the next two decades.

His opposition to school desegregation helped propel him to the governor’s mansion after a primary in 1984 in which desegregation was the leading campaign issue. Ashcroft called the desegregation plan illegal and immoral and paid for a plane to fly leading anti-busing leaders around the state to attest to his anti-busing bonafides.

Nixon on schoolhouse steps

In the fall of 1997, Attorney General Nixon appeared on the steps of Vashon High School, a crumbling symbol of black pride in St. Louis. He announced that he would press to end the transfer program and spend $100 million building new black schools in the city.

Opposition to desegregation did not turn out to be the political silver bullet that it had been for Ashcroft. Rep. Bill Clay, the one-time Jefferson Bank protester, convinced President Bill Clinton to pull out of a fundraiser for Nixon. Sen. Christopher S. Bond won a record number of votes in the African-American community to defeat Nixon for the Senate

But Nixon won a big court battle against Kansas City’s desegregation plan. This wasn’t the Supreme Court of Brown v. Board. The lone black justice was not Thurgood Marshall, who had won Brown, but Clarence Thomas, who had received his legal training alongside Ashcroft in Missouri.

Justice Marshall had thought segregated classrooms harmed black children by stigmatizing them as inferior. Thomas had a different idea of stigma. “It never ceases to amaze me that the courts are so willing to assume that anything that is predominantly black must be inferior,” he wrote.

Thomas was the deciding vote in the 1995 decision effectively bringing an end to school desegregation in Kansas City and to court-ordered desegregation nationwide - but not in St. Louis.

A political miracle

In 1998 Attorney General Nixon went to court trying to end the St. Louis program, but U.S. District Judge George Gunn Jr. wouldn’t go along. Instead, he appointed William Danforth, former chancellor of Washington University, to find a solution. The result was a settlement, approved by the Missouri Legislature, to continue the transfer program indefinitely. This settlement was built on three extraordinary accomplishments.

First, a coalition of rural and urban legislators in the state legislature combined to pass a law approving the continuation of the cross-district transfer program, even though the program had been politically unpopular in parts of the state.

Second, Danforth brought along the St. Louis business community, obtaining the support of Civic Progress, St. Louis’ most powerful business leaders. He told leaders the program had worked, resulting in much higher graduation rates for transferring black students.

Third, taxophobic citizens of St. Louis voted to levy a two-thirds of a cent tax on themselves.

In announcing the settlement of the case, Danforth called it “a historic day” for St. Louis. Minnie Liddell, the heroic mother whose suit had led to the desegregation plan said, “All I can say is, `Yay, St. Louis.’ This has been a long time coming, yet we have just begun. I’m glad I lived to see a settlement in the case.”

Liddell’s lawyer, Taylor, wrote that St. Louis’ settlement was the best in the nation. And nobody knew better than Taylor, who had been involved in many of the nation’s biggest school desegregation battles after having served as general counsel of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and then vice chair of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

“In many communities around the nation, courts are declaring an end to judicially supervised school desegregation and to the mandated subsidies for improved education that are often part of the remedy. But in St. Louis, the state Legislature has offered a financial package that will enable educational opportunity programs to continue for 10 years or more,” he said.

“Both from a financial and an educational standpoint, the St. Louis settlement is the best of any school district in the nation. The state funding will make possible continuation of the voluntary inter-district transfer program and the city magnet program. Both of these programs have enabled African-American city students to complete high school and go on to college at far greater rates than they have in the past.”

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial was headlined “Voting for a Miracle.”

“This feat makes us the first place in the nation where the democratic institutions of government found a way to preserve the gains of the era of desegregation while making it possible to improve the education of all children. Imagine. This happened in Missouri.”

Today, 17 years later, the transfer program continues to exist, although it involves fewer students.

Michael Brown’s School

The desegregation program didn’t desegregate public schools around Ferguson. The districts in the Ferguson area – Ferguson-Florissant and Normandy – became increasingly segregated.

Brown’s school, Normandy, is and was a failed district. State politicians and education officials have only contributed to its failure with chaotic decisions.

The state declared Normandy unaccredited in 2012 allowing its students to transfer to other school districts at Normandy’s expense.

Some suburban districts balked at accepting them, an echo of the qualms of some suburban districts when the city-county desegregation plan began 30 years earlier.

When Normandy students tried to transfer again in the summer of 2015, state education officials tried to block most transfers only to be overridden by the court.

The Missouri Legislature passed a bill to help out the district – by then broke and the worst performing district in the state -- but Nixon vetoed the bill because a school choice provision.

Meanwhile, the state displaced the Normandy school board and appointed the Normandy Schools Collaborative to take over. That group decided to hire temps from Kelly Services as substitute teachers.

Two hours after the announcement of the grand jury decision on Nov. 24, Michael A. Wolff, dean of the Saint Louis University law school, was asked on St. Louis On the Air - the radio program at St. Louis Public Radio - to explain the reaction in Ferguson.

“This particular incident and the reaction to it has built up on a whole lot of things people have grievances over…. The lives of the young people in our community particularly where Michael Brown lived and died were really impacted by some serious structural problems. For example, when (Normandy) failed and lost accreditation and some of the students could be allowed to transfer to other districts, some of the school districts told them we don’t want those kids.

“We have set up the system to be treating people unequally….Why are the school systems in that part of the community so underfunded compared to the ones you and I send our kids to?”

As Wolff spoke, the TV monitors in the radio studio showed the businesses of Ferguson going up in flames.